Buying a katana (or three).

by Ryan Gregory, April 29th, 2013I don’t currently train in any sword arts like Iaido or Kendo, but that hasn’t stopped me from wanting my own katana (Samurai sword) for a long time. The thing is, traditional katanas forged by a master swordsmith in Japan (nihontō) are not easy to come by, in part because they are incredibly expensive. In the past when I have looked, it seemed that the only alternative was a cheap knock-off that is useful only for display purposes (what are sometimes called “wall hangers”). But what I wanted was something in between — a well-forged sword that can actually be used to cut things (tameshigiri), but which doesn’t cost thousands of dollars.

I recently got another itch to buy a katana, and was pleasantly surprised to discover that a market has developed for functional but affordable swords. These tend to be manufactured in China, but the better ones use traditional Japanese techniques and can generate very high quality blades. In fact, there are now so many options that I found myself doing quite a bit of homework before I actually chose which sword(s) to buy. As such, I thought it would be useful for others if I shared some of what I learned. There are some excellent resources out there, including www.sword-buyers-guide.com and www.sword-manufacturers-guide.com. You can also Google any particular model you are interested in to find reviews.

1) Types of swords.

Katanas are the long, curved swords used by Samurai. There are also medium-length swords called wakizashi and much shorter swords (basically the length of a long knife) known as tantō. These all tend to be manufactured and styled in a similar way, and can often be found in a set.

These swords should not be confused with swords that have a similar blade but a simple wooden handle and scabbard called shirasaya. And definitely don’t confuse them with “ninja swords” (ninjatō), which may never have actually been used by real ninjas.

2) Forging and materials.

Traditional katanas are made from a kind of steel called tamahagane. In order to remove impurities, the swordsmith would heat the metal, hammer it, fold it, and repeat this process many times. This creates a very large number of layers of steel: 8 foldings gives 256 (28) layers whereas 16 foldings results in 65,536 (216) layers. It also leads to an attractive rippling pattern on the blade.

This process of folding isn’t strictly necessary anymore because modern steel is of much higher quality than what was available in feudal Japan. However, folded steel (sometimes called “Damascus steel”) katanas are still available and are actually somewhat less expensive than other options.

In general, the price of a sword is determined by the type of forging and the kind of steel used in the manufacturing:

i) The blade may be machine-made or hand-forged. Obviously, the latter is more expensive since it is much more labour-intensive.

ii) The blade may be through hardened or differentially tempered. Through hardened blades have a consistent hardness all the way through. Differentially tempered blades have an edge that is harder than the rest of the blade. One of the common ways to achieve this is to clay temper it (more on this later).

iii) The blade may be made of different kinds of steel which differ in physical properties and cost. Cost aside, there is also a trade-off between hardness (ability to hold an edge) and durability (ability to flex without breaking).

Below is a summary of the major types of steel that are used in modern katanas. You can also consult this very helpful guide.

i) Carbon steel. The most common types of steel used in modern katanas are 1045, 1060, or 1095 carbon steel. The number refers to the carbon content: 1045 has 0.45% carbon content, 1060 has 0.60%, and 1095 has 0.95%. Generally speaking, the more carbon, the harder the steel. 1045 carbon steel is the cheapest because it is softer and easier to work with, but it is often considered by collectors to be the absolute minimum grade for a functional katana (and many swordsmiths will insist on 1060 or better). 1095 carbon steel is more expensive but is much harder — possibly too hard (i.e., brittle) if it isn’t tempered properly. 1060 carbon steel is somewhere in between.

ii) Spring steel. As the name implies, spring steel is extremely flexible, allowing the sword to bend a great deal without breaking and return to its original shape without damage. The more common katanas that use this sort of metal are made of an alloy called 9260 spring steel, which contains 2% silicon. This is also used in fencing foils, which are subject to a lot of bending during use.

iii) T10 tool steel. Tool steel is a tungsten alloy steel which also has a high carbon content. It is extremely hard, and therefore holds an edge well and resists scratches. Note that some Chinese manufacturers refer to 1095 carbon steel as T10 steel, because obviously this wasn’t all confusing enough.

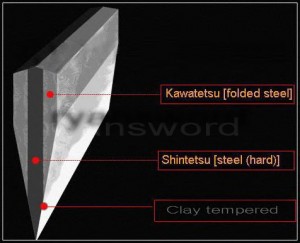

iv) Combined materials. Some swords use more than one type of steel, namely a harder type for the centre and edge and a softer kind for the rest of the blade.

An example of a combined material blade, in this case 1095 carbon steel in the centre and for the edge and softer folded steel for the outside. Image from www.ryansword.com.

BEWARE! Display swords are often made of stainless steel, which is fine for kitchen knives but is far too brittle for use in a long blade. These wall-hangers may also have the part of the blade inside the handle (the “tang”) spot-welded on rather that being made of a single, solid piece of steel. (You also want two holes for pegs that secure the blade to the handle, not just one).

The top image shows a spot-welded tang which can easily break and allow the blade to fly off. The bottom shows a proper “full tang” in which a single piece of metal extends into the handle of the sword.

Here’s what happens when you try to hit something with a stainless steel display sword:

3) Parts and options.

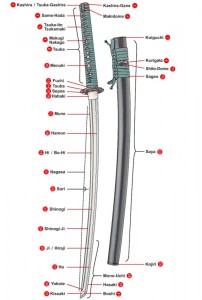

Here is a diagram showing the parts of a katana and their Japanese names:

I have found that the most relevant parts — that is, the ones that present options to consider when buying a sword — are the following:

i) Blade. In addition to the options based on different types of steel (see above), you will also see blades with and without a bo-hi (blood groove) and with or without a hamon (the visible pattern on the edge of the sword). Also, you will find both authentic hamons produced by clay-tempering and faux hamons which are purely aesthetic and are made either by acid etching or polishing. Only differentially hardened blades can have an authentic hamon. There are also options in terms of the type of edge, which affects the kinds of things that it can cut best, but I haven’t seen this as a common option within the lower price range.

An example of a blade with an authentic hamon and a bo-hi (blood groove). Image from www.ryansword.com.

ii) Tsuba (guard). There are tons of designs for tsubas, and different materials as well (iron, brass, other alloys). This really gives the sword a big part of its look, so get something you like.

iii) Other “fittings”. As with the tsuba, you can customize the other fittings including the little figures under the handle wrap (menuki), the ring below the guard (fuchi), and the cap at the end of the handle (kashira).

iv) Same (ray skin). Under the wrap on the handle, there is a strip of ray skin. This can be authentic (i.e., from an actual ray) or simulated and it can be a single piece or smaller panels. Authentic ray skin in a full piece is more expensive. The ray skin can also come in several colours.

v) Ito (wrap). The wrap on the handle is usually made of cotton, silk (or simulated silk), or sometimes leather. Purists will expect that the twists in the ito alternate in direction for historical accuracy, but personally I don’t care about this. For me, a more important issue is the colour, which along with the ray skin can really alter the look of the sword.

An example of a wrap in progress, showing the underlying ray skin (white) and ito (brown), with alternating twists. Image from www.sword-buyers-guide.com/Battle-Wrap.html.

vi) Saya (scabbard). The scabbards are typically made of wood and should fit tightly on the sword. These are most often black, but lots of options are available in terms of colours and patterns, as well as for the colour of the rope around the scabbard (sageo).

4. What I bought.

After reading about all of the above and checking out many different manufacturers, materials, and other options, I settled on the following swords to start my collection. I based my decisions on wanting to see swords from slightly different price ranges, different manufacturers, different types of steel, and different overall designs.

i) Musashi Wind Dragon katana.

This was the cheapest sword I bought, though it did get good reviews and is fully capable of real use. It’s 1045 carbon steel (I think) and hand-forged, though the hamon is cosmetic (I think). It has a bo-hi as well. The one thing I don’t like is that it has “CHINA” stamped on the seppa (spacer), but that’s a cheap part that can be replaced. I ordered this one from www.samuraisupply.com. You can find many other Musashi sword designs at www.musashiswords.com.

ii) Cheness Nagasa 9260 Spring Steel katana.

This is a larger than average sword, with a blade length of 30″ (versus a more typical 28″ or so). The handle is also longer than on my other katanas. It is made of through hardened 9260 spring steel, and is considered very durable. It comes with white ray skin and blue ito, and has a bo-hi. The tsuba is black in the shape of a crane. I ordered this one directly from www.chenessinc.com.

Here’s a different model (the “Tenchi”), but same basic sword:

(The deer was roadkill, btw)

iii) Ryan Sword Model 208.

This sword is 1095 carbon steel, clay-tempered with an authentic hamon, and no bo-hi. I particularly like Ryan Sword because they allow almost complete customization of all parts of the sword. I decided to keep the natural wood saya and the default fittings, though there were many options for these. I did, however, change out the ray skin (for black) and the ito and sageo (for purple). It’s a gorgeous sword, very well polished (more so than the other two), and very sharp. I ordered this one directly from www.ryansword.com.

I hope this information is useful, and if you’re interested in getting a katana I do encourage you to check out what is available these days. It is possible to get a very nice, fully functional sword for a very reasonable price. You just have to know what you’re looking for.

Helpful links:

- Authentic Japanese Swords: a Beginners Guide

- Real swords 101

- Common Sword Steels 101

- Sword care, cleaning, and repair

- Sword Buyers Guide

- Sword Manufacturers Guide

- Sword Forum

Vendors:

- Ryan Sword

- Cheness Cutlery

- Musashi Swords

- Samurai Supply

- Swords of the East

- Ronin Swords

- True Swords

- Hanwei Swords

- Heavenly Swords

- ProSwords

- Kult of Athena

- Swords of Might

- Swords.com

- Darksword Armory

- Sword and Armory

Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu

Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu

Kodokan Judo

Kodokan Judo

The quality of a katana really comes down to the forge. Many think that these mass produced carbon fiber blades that go through a quick cool process will hold up only to find otherwise.

Please be careful, both in use and storage. If you really want to do some tameshigiri I recommend getting some training first. Not only will it be safer but you will get a lot more out of it. Just like with a strike in Karate a sword cut can be done well or badly. You may not notice the difference if you are slicing pool noodles but why not learn it correctly?